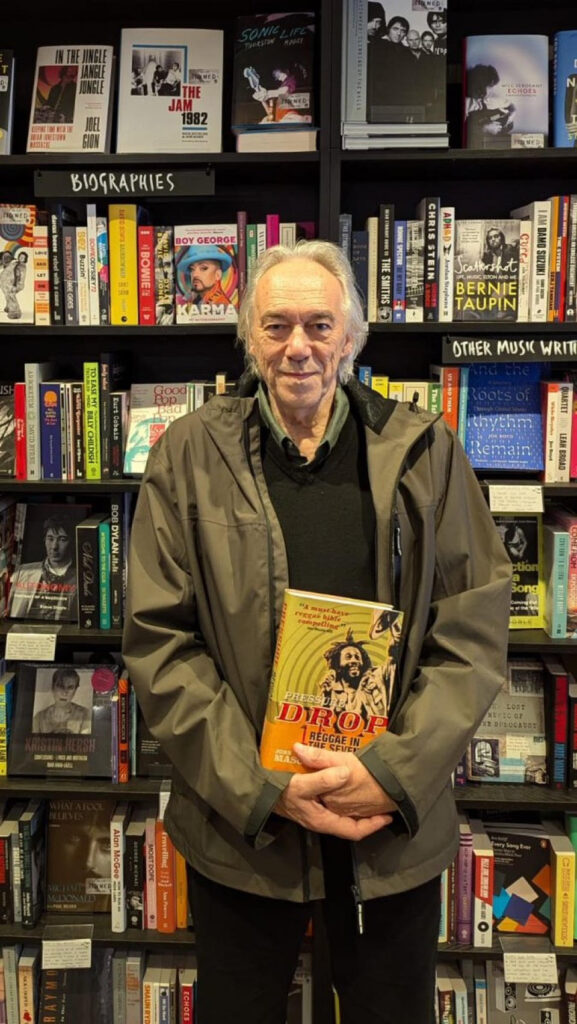

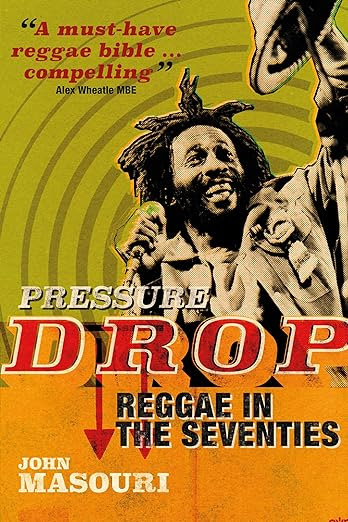

John Masouri‘s excellent Pressure Drop chronicles reggae’s most tumultuous decade. We question him about his book and the genre’s majestic vinyl output in the 1970s

Why was the 70s such a pivotal decade for reggae?

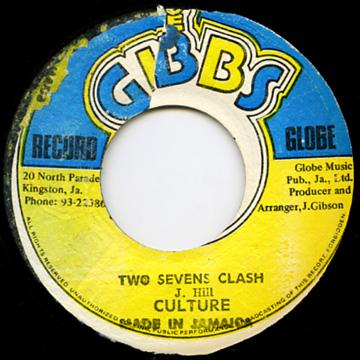

It was a decade in reggae history that offered an embarrassment of riches and a kaleidoscope of different forms, sounds and innovations. It started with the rise of deejays: artists who pioneered the art of rhyming verse on records and who sparked a global love of rapping, since there was no hip-hop when Count Machuki and Sir Lord Comic first strutted their stuff on local sound systems. A cultural revolution began when Count Ossie took the sounds of nyabinghi drumming from the Rasta camps and into the consciousness of young rebels such as Bob Marley and the Wailers.

We also witnessed the coming of dub – a Jamaican art form where music was freed from all the usual strictures and delivered into the hands of magicians like King Tubby and Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry, whose ability to manipulate sound would attain near mystical qualities.

Pressure Drop unfolds chronologically and each year of the decade has its own dedicated chapter. Was there a reason for this structuring?

I decided to write the story of 1970s reggae in the way I did – as it unfolded – because that’s how I, and fans of the music, first experienced it. We eagerly awaited each new release or tour, and read about the latest developments in the music press or news reports from Jamaica thanks mainly to The Voice and Daily Gleaner. There was a lot to write about, especially after weaving in the political turmoil that permeated the consciousness of musicians on both sides of the Atlantic.

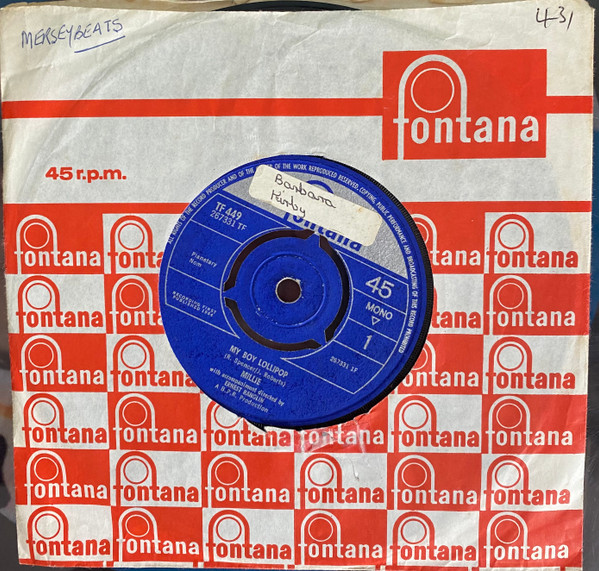

I know you’ve spoken about your love of this 45 before, but how important was Millie’s My Boy Lollipop in the UK?

I was too young to experience My Boy Lollipop as a 45. But it was the combination of the sight of a vivacious girl singer from Jamaica – my first crush, aged 11 – and the sound and excitement of a ska genre that was just as new, exciting and vibrant, which proved such a heady mix back in 1964. While it wasn’t a Jamaican record per se, having been recorded in London, it was a first for the UK pop world and the beginning of a lifelong love affair for many people of my generation.

Wasn’t the initial Jamaican music scene driven by 45s and not LPs? When did reggae LPs start to gain popularity?

All of the music I grew up listening to – pop, Blue Beat, rock and soul – was almost entirely experienced via 45 singles and EPs, whether heard at school, friends’ houses, on the radio, the occasional TV show like Ready Steady Go! or Top of the Pops, and jukeboxes in coffee shops. And a little later on, in clubs and shebeens. LPs were something that we got for Christmas when I was of school age, and only became culturally significant in the hippy era, once the Beatles released Sgt. Pepper’s. Reggae LPs took much longer to attain that kind of status and were mostly singles collections back then. Trojan’s Tighten Up and Pama’s Straighten Up series were very popular, but that wasn’t where my own vinyl journey started. My first 45 (Hey Joe), LP (Are You Experienced) and gig (a package tour also featuring Pink Floyd with Syd Barrett) all centred around Jimi Hendrix. It was the 1968 reissue of Prince Buster’s Al Capone that started the flood of Jamaican releases to my red Dansette, and I still consider it a cornerstone of Jamaican dancehall music.

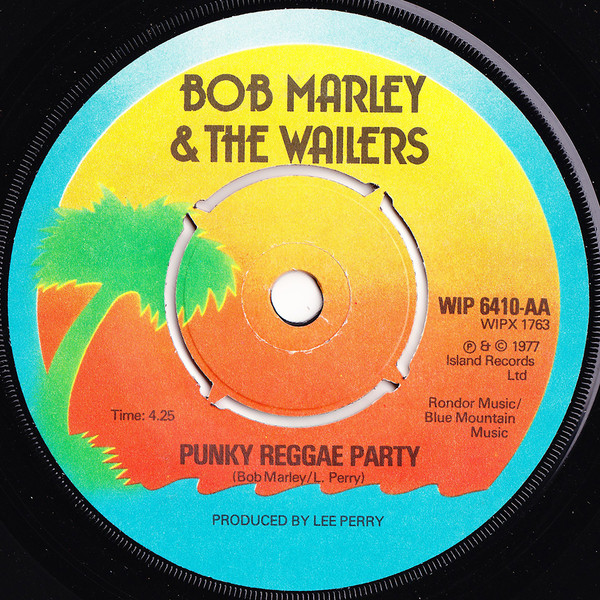

Punk and reggae formed an unlikely alliance in the 1970s, culminating with Bob Marley’s Punky Reggae Party. Why did the two genres associate with each other so closely?

I’m not convinced they did “associate with each other so closely”, as I’ve yet to meet a Jamaican reggae musician who actually liked punk music! Most admired the spirit and rebellion in punk, but reggae was almost always about the betterment of society, and the nihilism of punk was far removed from what the majority of 1970s reggae songs were trying to express. It was certainly helpful in terms of exposure for reggae acts to tour and share a bill with punk bands here in the UK, but I can’t think of any punk groups who performed in Jamaica, or toured with reggae acts to any notable extent. Like it or not, but US soul and R&B, and also rock music – the Stones, Eric Clapton, Joe Cocker – had a far greater involvement with (and influence on) reggae than punk. Incidentally, there’s a quote from Chris Blackwell in Pressure Drop where he says he hated Punky Reggae Party and thought it was the worst record Bob Marley ever made. I must admit, I’m not keen on it either!

Richard Branson’s Virgin and Chris Blackwell’s Island labels seemed to be in competition to sign up as many of Jamaica’s artists as possible in the 1970s. Was it a genuine rivalry?

It’s no accident that reggae flourished like never before when both Island and Virgin were signing acts and promoting the music just as they would rock acts, by ensuring people could buy it in high street shops and read about it in the popular music press. I’ve never met or interviewed Richard Branson, but people close to him have said that he has great respect for Chris Blackwell. The latter once told me that he welcomed Virgin’s involvement as it could only help strengthen reggae’s market share. And let’s face it, there was plenty of talent to go round!

It seems incredible now that Althea & Donna had a No.1 hit – was this the pinnacle of reggae’s mainstream appeal in the 1970s?

Uptown Top Ranking wasn’t just a success in the UK – it was also a No. 1 hit in Jamaica. That’s because it was very catchy, sounded great on the radio and was delivered by two young uptown girls, deejaying with appealing innocence over an infectious hit rhythm. What was there not to like? It proved to be a one-off, but anyone looking for the nadir/pinnacle of reggae’s “mainstream appeal” should look first in the direction of Boney M!

Bob Marley aside, how successful were the other Virgin/Island artists?

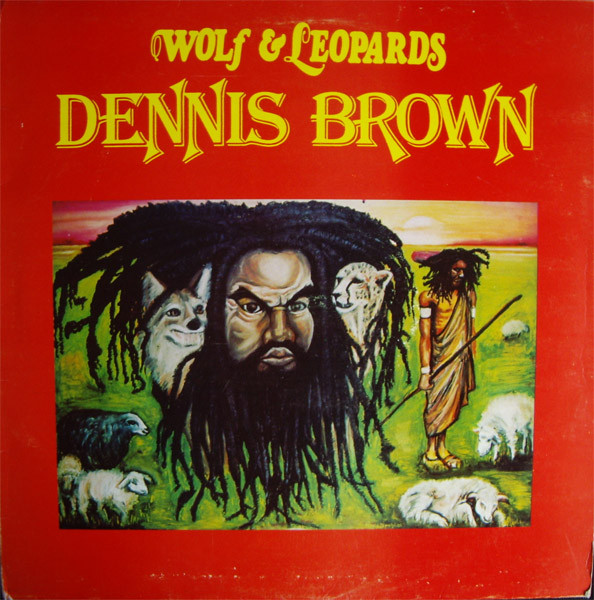

The sheer volume of Virgin and Island reggae releases during the 1970s should tell us that both labels were making sufficient money from the genre to justify their involvement, and there was a multitude of other independent labels who contributed to the total during that era. Marley didn’t have his first crossover hit until late 1975 and never had a commercial hit in the US during his lifetime. But while he became reggae’s main figurehead, I doubt he ever saw himself as being separate from what other reggae artists were doing. It was overseas journalists who made those distinctions, using the same old divide-and-rule tactics that inevitably surface when discussing… well, anything really. We’re conditioned to think it terms of winners and losers, rather than embracing the totality of anything. The irony is that among reggae’s grassroots audience, Dennis Brown was arguably more popular than Marley. We certainly heard Dennis Brown a lot more often in reggae clubs and dances. I’d say that Marley was widely respected, but Dennis was both respected and loved – that was the difference.

There were some fantastic UK reggae artists that broke in the 1970s. Who do you think were the best of them?

I think most fans would agree that Steel Pulse, Aswad, Misty in Roots, Matumbi, Linton Kwesi Johnson, Black Slate, Greyhound, the Cimarons and Janet Kay were among the frontrunners, and their most well-known records are invariably representative of their best work. It was during the 1970s that UK reggae found its voice and discovered a distinct identity of its own, rather than trying to copy what was happening in Jamaica. What we have to remember is that whenever a reggae act was granted airplay and exposure here in the UK, their records invariably did well. Reggae music’s popularity with the British public hasn’t really been in doubt since the late 1960s, but talk to old-timers and they’ll tell you it was prevented from realising its true potential by the lack of proper distribution and promotion. I still don’t believe UK reggae of any era – with the exception of 2Tone – has received the respect and attention it deserves, hence the expression “half the story’s never been told”.

Is dub a 1970s phenomenon? Versions appeared on the B-sides of 45s, but how did the music evolve into a distinguishable sub-genre? Is Keith Hudson’s Pick a Dub part of the story?

Just like deejaying, rockers and songs about herb and Rastafari, dub certainly became part of the reggae canon in the early 1970s, and I write about this at length in Pressure Drop. Bunny Lee once announced that there’s no absolute truth when it comes to Jamaican music, only versions. Both Herman Chin Loy (Aquarius Dub) and Randy’s Clive Chin claim to have recorded the first-ever dub LP, although Prince Buster was among the early pioneers where that was concerned too, so who knows? What’s beyond doubt is that Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry and King Tubby – aided and abetted by Bunny Lee’s formidable marketing skills – did most to popularise dub music and, together with Errol ‘ET’ Thompson and producers such as Yabby You, Keith Hudson and Glen Brown, helped elevate it to one of the most thrilling and inventive musical art forms of the 20th century. It’s strange to think that, by the mid-1980s, dub had become devalued by the sheer number of (often) poor quality albums released in a relatively short period of time. Yet, this strictly Jamaican offshoot has continued to exert a tremendous influence on popular music.

As a footnote, Pick a Dub was notable because the rhythm tracks featured the drum-and-bass pairing of Carlton and Aston ‘Family Man’ Barrett, who also played on all of Bob Marley and the Wailers’ hit records. It also got a UK release courtesy of Atra – a label owned by Brent Clarke, who had close ties with both Island and Virgin.

Can you direct us to the reggae sounds of the 1970s we should be listening to? Perhaps a Top Ten?

There’s such a wealth of albums covered in Pressure Drop, featuring singers, deejays, instrumentalists, vocal groups, nyabinghi drummers and dub poets, and of all types including dub, slackness, roots and culture, 2Tone, punk, easy listening and fusion, that I couldn’t possibly narrow it down to just ten.

In fact, to do so would negate the rich variety I’ve attempted to portray over the course of its 600-plus pages. However, I’ve compiled Spotify lists of singles from each year covered in the book – namely 1970-79 – and so hopefully listeners to those will gain some idea of how the music developed throughout that decade. I would urge readers to have Spotify or YouTube at the ready as they turn the pages, and enjoy the ride…

Pressure Drop: Reggae in the Seventies (£28) by John Masouri is a published by Omnibus Press. Buy it here.