Author and record collector Jonathan Scott‘s latest book, Into The Groove, expertly chronicles the history of recorded sound and the science behind it. We twist his arm for information

Your book is subtitled The Story of Sound from Tin Foil to Vinyl. How exactly does tin foil enter the equation?

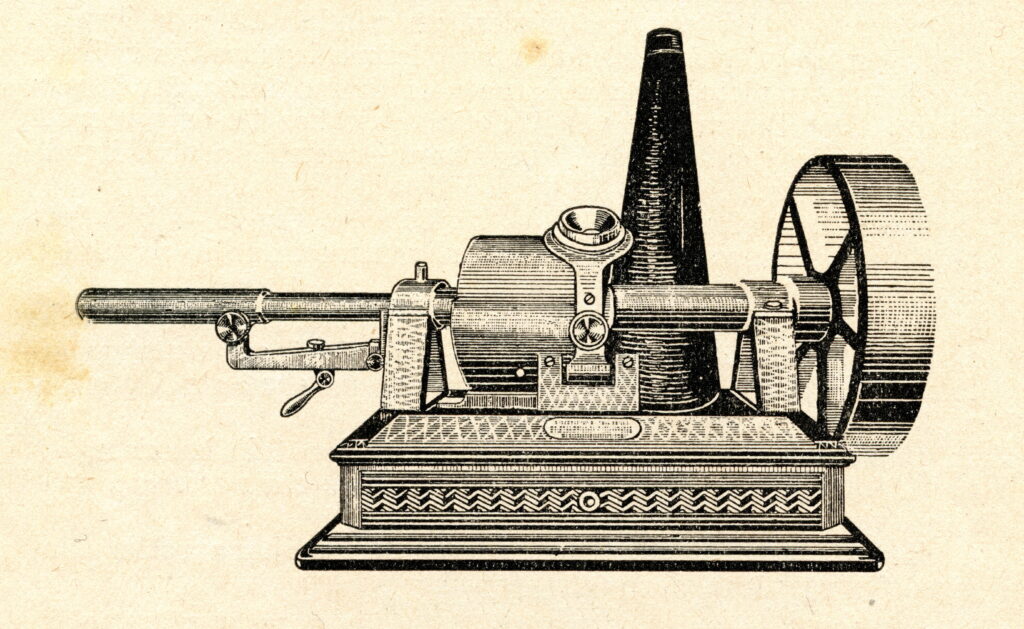

Thomas Edison’s original record player, the phonograph, recorded on foil. It was created in the second half of 1877, a by-product of a project to invent a new type of telephone. It had a grooved metal cylinder around which you wrapped tin foil. You turned the hand crank and bellowed into a mouthpiece. This vibrated a diaphragm with a needle on it – the needle then imprinted the sound waves into foil. Being tin foil, it didn’t sound great and recordings only really survived one or two plays. Removing the foil to make another recording destroyed the original recording. So while it was undoubtedly a sensation, it was also really annoying and largely useless.

It seems as though Thomas Edison invented everything back in the day. What was his role in pioneering the sound recording process?

Edison’s great skill was not only inventing stuff, but a laser-like focus on utility and profitability. The phonograph itself proved to be tricky. Those foil machines weren’t very useful and cost a lot to make. So he became distracted by other more profitable ventures, and the phonograph fell into relative obscurity. It wasn’t until a decade later, when a competing workshop launched a much better device called the graphophone, which recorded on narrow card tubes covered in wax, that Edison came back to the table. He launched a series of much-improved, battery-operated prototypes that recorded sound into solid wax cylinders, which could be shaved and reused. It was these machines, from 1888 onwards, that ushered in the birth of the recording industry.

“Taking in the one-two punch of cassette tape and compact disc, it’s genuinely surprising that vinyl survived the 1980s and 1990s”

How serious a contender was the wax cylinder? And when were they seen off?

Many cylindrical records, particularly the Blue Amberols Edison launched in 1912, sounded better than contemporary disc records. This was partly because they used vertical (rather than lateral) cut grooves, and partly because the stylus went over the surface at a constant speed. With discs, the speed gradually reduces as the needle reaches the centre of the record, impacting sound quality.

The first disc records, which were stamped onto a kind of hardened rubber, sounded bad. Indeed, the very first were so bad they had the words that were being said printed on the reverse to help the listener interpret the sounds. But even these earliest discs scored over cylinders in important ways. There was no way to mass produce recordings with early cylinders. So if someone wanted to sell ten copies of a song, they had to perform the song ten times. Whereas those first discs could be stamped out from a single master recording. This made them considerably cheaper to produce. So even though cylinders clung on until 1929, the moment discs started sounding really good – from around the turn of the century – the writing was on the wall.

Could Emile Berliner lay a claim to being the godfather of vinyl records?

Yes, definitely. He pioneered disc-shaped records, beginning his experiments in the 1880s and launching the first commercially available discs a few years later. He would go on to form the Gram-o-phone company, whose UK arm would eventually morph into HMV.

When did 78s arrive on the scene?

Berliner was looking around for a better material with which to make his records – rubber wasn’t cutting it. In 1895 he sent a nickel-plated stamper to the Duranoid Company in Newark, NJ, which was making electrical parts using a shellac compound. The results were much better than anything he had tested to date and very soon all Berliner discs were being made by Duranoid.

Meanwhile, sound engineers found that the best balance of sound quality and runtime was achieved at around 80 revolutions per minute. To achieve that speed, using common components available at the time, you combined a motor that ran at 3,600 rpm with a gear with a ratio of 46:1. This resulted in a speed of 78.26 revolutions per minute.

Was there a golden age of 78s?

Among collectors, it’s jazz/blues discs from the 1920s and 30s that are most desirable. Others focus on the acoustic era – stuff recorded before 1925, without the use of microphones. Remember, 78s were the dominant format for half a century. During that time, while recording processes slowly improved, the way discs were made didn’t change much. They experimented with different speeds, chemical compositions, sizes, cuts and groove widths, but overall, the format stayed unchanged, broadly divided into ten-inch for ‘light’ music, 12-inch for classical. And although many of us associate 78s with poor sound quality, it’s really not the case. If you get a clean, early 1950s shellac 78, and play it with a nice fresh needle, it sounds great!

Why is 1948 such an important year in the history of vinyl records?

People had tried various methods to increase the runtime of shellac records. In the 1920s, Edison launched an early long-playing record by simply increasing grooves-per-inch from 150 to 450, giving around 20 minutes per side. They went with a slogan that promised music “from Soup to Nuts”! This didn’t work very well – the grooves were just too fragile. RCA also launched a long-player in the 1930s, but the economic climate wasn’t right and it was shelved.

Columbia launched its 33 rpm LP micro-groove vinyl record at the Waldorf Astoria Hotel in New York, in June 1948. An A&R man stood before two piles of records – one several feet high, the other up to around the knee. Then he told the audience that both piles represented exactly the same amount of music. RCA launched their competing seven-inch 45 rpm record the following year, kicking off the so-called “speed wars”.

“I would begin to enthuse about MiniDiscs, but I got rid of mine a few years ago and the decision still haunts me”

When did hi-fi become a thing?

In the 1930s and 1940s, engineers and cutters would tailor the equalisation curve – limiting bass response and boosting the treble. In theory, this would translate well once records were spinning at home, as home sets tended to restore bass and bring down treble. However, the actual recording curve tended to vary between labels, meaning two records might sound very different – overly boomy or overly bright. So, enthusiasts began making their own equaliser circuits. Ones they could switch depending on the maker of the record – one labelled HMV, another labelled Columbia, and so on.

However, it was really in the 1950s, when an economic upturn, vinyl’s reduced surface noise and widespread use of magnetic tape combined to make high quality home audio within reach for many.

When did 33s and 45s hit their peak in terms of sales?

Peak LP sales was 1977. The UK’s biggest year for seven-inch records was 1979 – with around 79 million units sold. More interesting, though, is the changing market share – 1974 vinyl sales had about a 70 percent market share in America, with 8-Track 25 percent and cassette at five percent. By 1980, cassette had leapfrogged 8-Track, overtaking vinyl in 1983. CDs overtook vinyl in 1986, and cassettes in 1990.

When was the 12-inch format introduced? And what function did it serve?

It was during the disco era. Nightclub DJs would get two copies of a record so they could flip between them, creating their own extended mixes. This trend was helped by record companies who began issuing some singles with instrumental b-sides. Then DJs worked direct with record companies to produce their own unique, one-off mixes, and the labels in turn began pressing occasional 12-inch promotional discs.

There were technical advantages – a 12-inch record, with only one song on it, has much more real estate, meaning wider spaces between the grooves, meaning louder levels and wider dynamic range. This ultimately culminated in Ten Percent by Double Exposure, released by Salsoul Records in May 1976. This was the first 12-inch single to be commercially issued to the public.

How quickly did CDs take vinyl down?

Looking back, taking in the one-two punch of cassette tape and compact disc, it’s genuinely surprising that vinyl survived the 1980s and 1990s. CDs sounded amazing, there was no jumping or static, they were a convenient size, you could be a bit rougher with them and they wouldn’t mind. But if you look at the history of records as a whole, this happens over and over. Look at radio in the 1920s – many predicted it would see off 78s. Here was a box you plugged in, tuned to a station and it gave you music for hours on end.

As a record collector yourself, what is your favourite format?

Vinyl, is the short answer. The longer answer is that I love formats. I’m fascinated by the way sound shaped technology and technology shaped sound – the way cylinders popularised the three-minute pop song, the way 78s dominated for nearly half a century, the way the first LPs were really designed with classical music in mind and yet helped shape popular music’s unit of currency: the album. I think it’s partly because I grew up in a household filled with archaic formats – a polyfon, a pianola, a Betamax video player, a MSX computer – and partly because there are certain formats that feel so right in your hand. Vinyl is one of these. And at this point, I would begin to enthuse about MiniDiscs, but I got rid of mine a few years ago and the decision still haunts me.

THE STORY OF SOUND

Jonathan Scott has kindly lent us this groovy timeline, which outlines the history of recorded sound

1853/4

Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville makes the phonautograph, the first device for recording airborne sounds. These could only record, not play back. In 2008, firstsounds.org successfully reconstructed the sound of Scott de Martinville singing – a recording made on lampblacked paper, 17 years before Edison invented the phonograph.

1877

Parisian poet Charles Cros writes a letter containing a method for recording and playing back sound. He is without the funds to develop his idea.

Thomas Edison plays back his own voice saying “Halloooo”, recorded on a strip of paper at Menlo Park, New Jersey.

The first hint of a new sound recording invention is published in a letter to Scientific American.

On 29 November, Swiss-born machinist John Kruesi is handed a sketch by Edison. Kruesi builds the phonograph. The first successful playback from this tinfoil cylinder phonograph (Edison saying “Mary had a little lamb”) takes place on 6 December.

The tinfoil phonograph is demonstrated at the New York City offices of Scientific American.

Demonstration phonographs tour the world, generating interest and coverage. However, these were expensive, unreliable and hard to use. Edison’s attention turns towards electric lightbulbs.

1880s

Alexander Graham Bell sets up the Volta Lab in Washington DC. With Massachusetts-born engineer Charles Tainter, they begin working on an answer to the phonograph. They produce a vast array of prototypes, including the first lateral-cut (or zig-zag) record in the summer of 1881.

1885

Earliest recorded swear word. Volta Labs, Washington DC. The speaker is thought to be Volta Labs associate Harry G. Rogers, and the word is thought to be “fuck”.

The Volta team finally launch a second generation phonograph. The graphophone uses wax-coated card cylinders, incised with vertical-cut/’hill-and-dale’ grooves. It’s aimed at the business community – a cylinder could record a few minutes of dictation, which could then be handed to typists.

1887

A third type of record appears, made by German-American Emile Berliner. He’s granted patent 372,786 for the gramophone, which uses a disc, photo-engraved with a lateral-cut groove.

Edison launches a much improved phonograph, now with a battery-powered electric motor and wax cylinders.

1888

Berliner demonstrates his gramophone at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia. He uses a one-sided seven-inch disc with lateral-cut grooves, hand-cranked at 30 rpm with a capacity of roughly two minutes.

Oldest recording of a public performance – Handel’s oratorio Israel in Egypt, 29 June 1888, 2pm, Crystal Palace, London. It is recorded from the press gallery by Edison representative, Colonel Gouraud.

1889

A log book from Edison’s laboratory records the company’s first forays into recording music. The first entry, from 24 May, notes a series of flute recordings by Mr F Goede. The log book is known as the ‘founding document’ of the recording industry.

A Washington DC court reporter named Edward Easton forms the Columbia Phonograph Co. The first record label catalogue is printed the following year.

First commercially issued Berliner discs are made by German toy makers. These are tiny and made of rubber. Sound reproduction is so poor that they come with the text of what is being said on the reverse.

1896

Berliner begins using shellac from the Duranoid Co in Newark, NJ. This makes better sounding records than hard rubber.

1897

Eldridge Reeves Johnson creates a simple and reliable disc phonograph that becomes a bestseller. His company merges with Berliner’s, forming Victor Talking Machine.

1898

Gramophone Company, based in the UK, is founded by Berliner. American musician Fred Gaisberg joins the Gramophone Company in London as its first recording engineer.

English artist Francis Barraud paints a Jack Russell Terrier, named Nipper, listening to a wind-up cylinder phonograph. Once modified to a disc gramophone, the image is used for the His Master’s Voice (HMV) label in 1901. It will also become the trademark and logo of the Victor Talking Machine Company, later known as RCA Victor.

1900

Thomas Lambert develops a successful method of mass-duplicating ‘indestructible’ cylinders.

1902

Edison introduces ‘Gold Moulded’ cylinders – mass-produced by a moulding process.

Fred Gaisberg is rapidly becoming one of the first modern record producers, nabbing performing stars of the day for the Gramophone Company. In 1902, he records tenor Enrico Caruso, paying Caruso £100 out of his own pocket. The resulting records are a sensation.

Victor introduce an all-enclosed cabinet phonograph, advertised as the Victrola upright. Victrola becomes the name for phonograph players with interior sound-projecting horns.

The first albums begin to appear – collection of 78 rpm discs collected together in a binder.

78.26 rpm becomes the standard for motorised phonographs because it was easily achieved using a standard 3600 rpm motor and 46-tooth gear (78.26 = 3600/46).

1912

Edison’s Blue Amberol is the last incarnation of the cylinder line for the Edison Company. These could boast a 4:45 runtime. Having argued against discs for a generation, the firm introduces the Edison Diamond Disc. The last Blue Amberol is made in 1929.

1925

Pre-1925, sound recording is known as the Acoustic Era. The Electric Era begins when new Western Electric condenser mics allow engineers to capture a greater frequency range. The Magnetic Era (from 1945) sees studios use magnetic tape to record masters ahead of cutting records. The Digital Era begins in 1975: the first all-digitally-recorded LP is Ry Cooder’s Bop ‘Til You Drop in 1979.

1931

Alan Blumlein at EMI files a UK patent for a new means of stereo recording and reproducing. Stereo reproduction is pioneered by the film industry, but it takes a long time to filter down to domestic record buyers.

1948

The first vinyl record is introduced at the soon-to-be standardized 33 1/3 rpm speed by Columbia Records. It uses micro-groove plastic to extend a 12-inch record’s runtime to 21 minutes on each side.

RCA Victor presses its first 45 rpm seven-inch vinyl record – PeeWee the Piccolo. They come with a wider play hole at the centre, designed to work better with auto-changers.

For a generation, the new vinyl speeds coexist with shellac 78s.

1952

Emory Cook creates a stereo record using two separate channels, in two separate groups of grooves, played using a twin-headed cartridge mounted on a tonearm.

1957

In November, the small Audio Fidelity Records label releases the first mass-produced stereophonic disc. Side one featured the Dukes of Dixieland, side two sound effects. From this period, albums began to be sold in both mono and stereo.

1977

LP sales reach their global peak. The Voyager Golden Record, designed to spin at 16 rpm, containing 90 minutes of music, 120 images, greetings and sound effects, is launched into space aboard the Voyager 1 and 2 space probes.

1979

Sony launch the Walkman.

1982

The first compact discs go on sale. One of the stories is that they are 120mm wide because Sony insisted Beethoven’s entire 9th Symphony (74 minutes) should be able to fit on one disc.

1997

MP3.com is founded. This is a forerunner to the likes of Spotify and Apple Music, designed to allow musicians to easily share content.

2001

Apple launches the iPod.

2006

Daniel Ek and Martin Lorentzon found Spotify, aiming to create a legal alternative to file sharing platforms.

2008

Global sales of LPs go up for the first time since 1984.

2022

Vinyl albums outsell CD albums for the first time since 1987. The US also saw its biggest week for vinyl since 1991, selling 2.2 million LPs in the week ending 22 December.

Into the Groove: The Story of Sound From Tin Foil To Vinyl by Jonathan Scott is published by Bloomsbury (paperback, £12.99). Buy it here.