Music journalist and cultural historian Jon Savage tells Groovy Times about how he went from making mix-CDs for friends to curating much loved compilations for labels such as Caroline True and Ace Records

When it comes to putting together compilations, Jon Savage doesn’t like to over-complicate matters. “The basis of compilations as far as I’m concerned is, ‘I like this stuff, you may like it too,’” he says. “It’s really simple.” Except, of course, while it may be a straightforward matter to run favourite tracks together, especially in the age of Spotify playlists, creating compilations that tell a story and resonate with a wider audience is rather trickier.

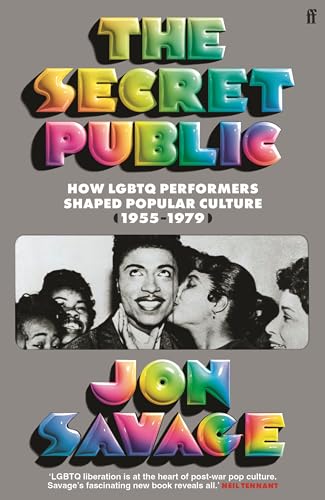

This is something at which Savage is adept, which perhaps shouldn’t be surprising. As anyone who has read Savage’s books – which range from his magnificent account of the punk era, England’s Dreaming: The Sex Pistols And Punk Rock (Faber, 1991), to his meticulously researched The Secret Public: How LGBTQ Resistance Shaped Popular Culture (1955-1979) (Faber, 2024) – can testify, he’s someone whose taste reaches out far into the hinterlands of popular music. More than this, his writing at its best makes you long to hear records you’ve never before encountered or helps you find the magic in tracks that might otherwise seem overly familiar.

Who better then to speak with about the art of the compilation? Here, Savage reflects on both on his own work compiling albums and on the broader cultural history of compilations – especially Nuggets and its influence on punk.

How did you get started making compilations?

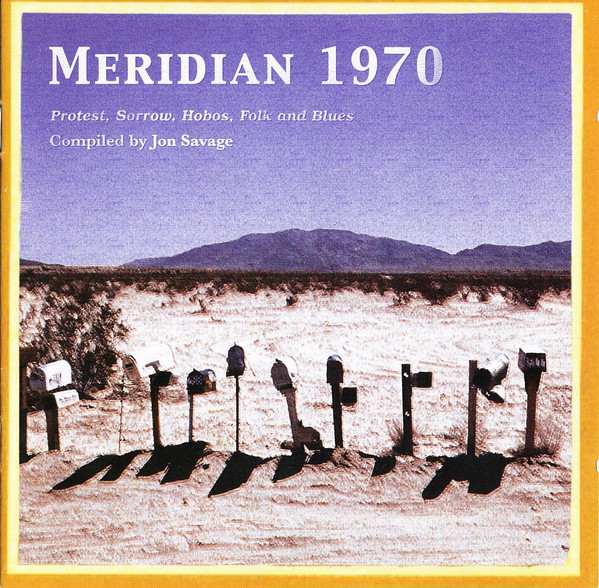

I turned 50 in 2003. I had some friends of the same age and we had a day we spent playing records from the early ’70s. And records from the early ’70s were distinguished by the fact that, although they were usually not very good, there were one or two great tracks on them. It was also an era of total overproduction, if you’d been in a successful 60s band, you got a solo album. Anyway, we were playing the best tracks of these albums and I put them onto CDs for friends, and I gave one to Jeff Barrett of Heavenly. And Jeff said, “Let’s do a compilation out of it.” And that became Meridian 1970 (Protest, Sorrow, Hobos, Folk And Blues) (Forever Heavenly, 2005) which I was very pleased with and I regard as the first proper compilation I did.

You have compiled a long series of compilations for Ace Records, each of which encompasses a specific year. How did that come about?

I’d written a book, 1966: The Year the Decade Exploded (Faber, 2015), and I thought it would be a good idea to have a compilation to go with it. I was friendly with Roger Armstrong at Ace Records and I said, “Well, what about doing a compilation?” And that’s when the years started. We’ve done nine of them now [albums that range chronologically from Jon Savage’s 1965: The Year The Sixties Ignited through to Jon Savage’s 1983-1985: Welcome To Techno City].

What are the practical constraints? You’re never going to be able to licence The Beatles.

Or the Stones, or Eric ‘bloody’ Clapton. I’m working on a new compilation and I wanted My Bloody Valentine but we can’t get them. Often there are legal situations, or people are too greedy, or major labels, to be honest, can’t be arsed, although some major labels are very good. So the licensing can actually really difficult. I usually make three CDs and then I send them to Liz Buckley at Ace Records. We whittle the selection down to two CDs and then work from those two, so that when we’re knocked back there are extras we can use that have already being selected.

Which of your compilations has worked best from your perspective?

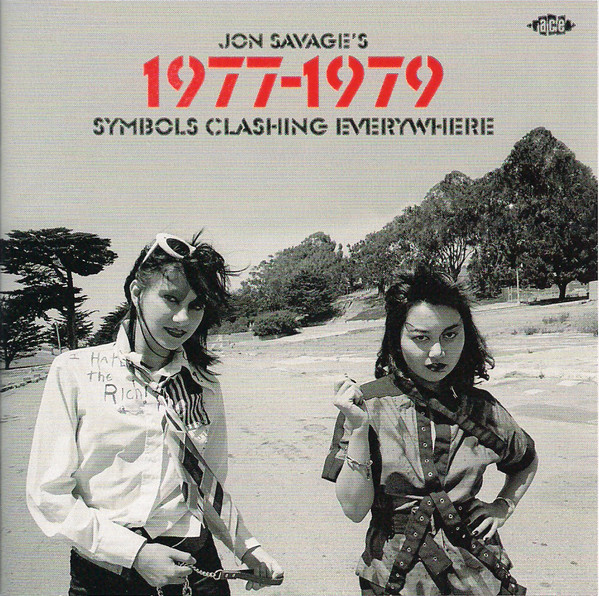

I really like 1977-1979: Symbols Clashing Everywhere because it’s very diverse. Most punk compilations just have punk, so they start with The Ramones and then you end up with The Skids or The Ruts. And that’s just boring, it’s been done a hundred times. 1977-1979 has a lot of dub reggae in it, a bit of synthetic disco, and then moves into what happened in ’78-’79 which is a great, opening out from punk energy into all sorts of avant-garde electronic disco, British electronic disco, all that sort of stuff, people like Wire and The Slits too. It was a real mixture. And that was my experience at the time. Although I was writing about punk a lot, I didn’t just solely listen to punk, I listened a lot to other kinds of music as well.

Going back, what about the cultural significance of complications?

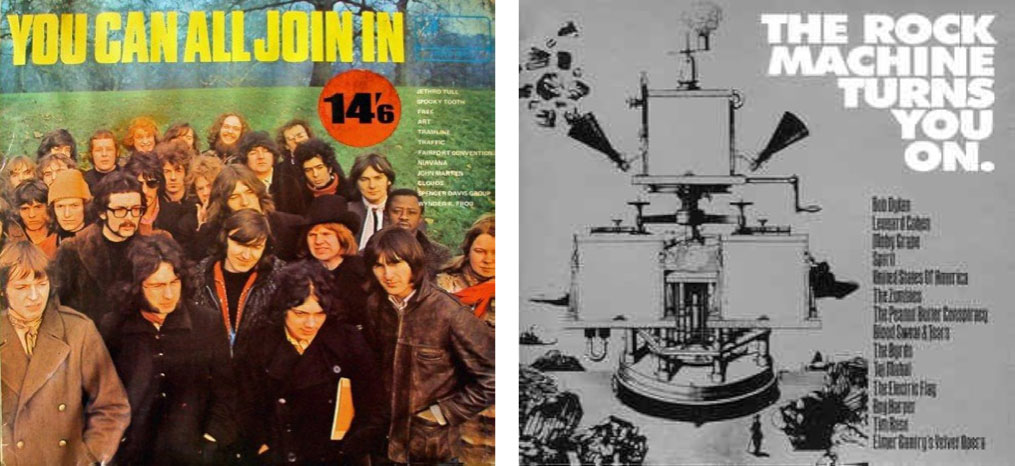

They were cheap, that was the main thing. You Can All Join In (Island, 1969) was really cheap, and it actually holds up very well, although The Rock Machine Turns You On (CBS, 1968) is a bit too diverse. I can’t remember how much these albums cost, but they were definitely under a quid, when most LPs would be, you know, 32/6 or something. So they were probably half the price of a normal LP and they became a big thing.

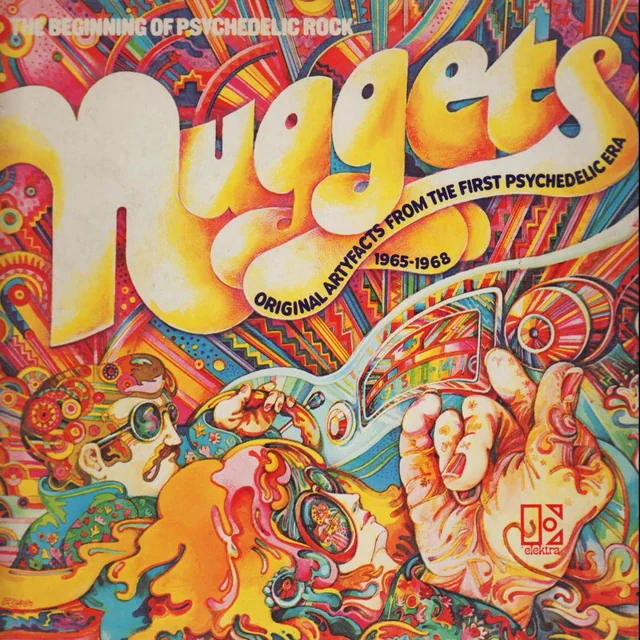

But Nuggets (Elektra, 1972, reissued by Sire in 1976) was the game changer, because that was curated [by Lenny Kaye, later of The Patti Smith Group], and it was presenting an aesthetic and a moment in time, and it used the word punk. Most people in Britain had never heard these records because they were only regional hits or American hits, they weren’t UK hits. Nuggets was a complete revelation.

Did you realise at the time how important Nuggets would become?

It was very niche. Nobody else I knew had it, but I used to play it to people and they really loved it. I just like the directness of it. I’ve always liked direct, loud guitar noise, which is why I liked punk. And I like the sound of these records because they remind me of my ’60s favourites, like the Yardbirds, who American garage bands took from. Them were big favourites of mine as well.

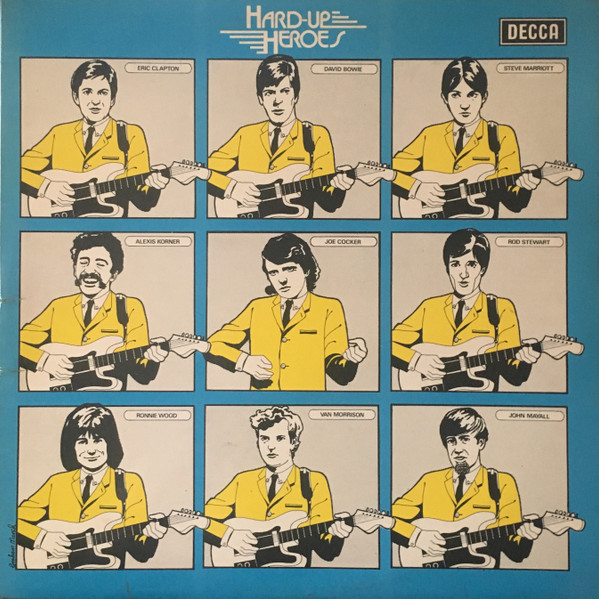

I talked about this recently with Rob Symmons, who was in Subway Sect and now The Fallen Leaves, and is a real aesthete of the pre-punk period. He talks not just about Nuggets, but also other compilations that happened in its wake, such as Hard-Up Heroes (1974), which was a Charles Shaar Murray and Roy Carr-compiled double LP they made for Decca, which had stuff like The Poets and Joe Cocker’s first record. Also Andrew Lauder did a compilation for United Artists called Mersey Beat ’62-’64: The Sound Of Liverpool. These mined this energetic, fast ’60s feel and that really went into punk. When I first saw The Clash, they reminded me of The Who and The Kinks for a different time. Or it was almost like seeing The Birds sped up for a decade later.

Finally, are you working on a compilation at the moment?

I’m doing a compilation covering 1986-90 which should probably be the last chronological one. I still have a couple of ideas for compilations after that, so you know, I’m not gonna stop!

Jon Savage was talking to Groovy Times‘ Jonathan Wright. Many thanks to Ace Records for the hook up. His latest book is The Secret Public: How LGBTQ Resistance Shaped Popular Culture (1955-1979). There’s also an accompanying compilation from Ace (CD only), Jon Savage’s The Secret Public: How The LGBTQ+ Aesthetic Shaped Pop Culture 1955-1979.