After experiencing a sonic epiphany on the bus, Groovy Times guest writer Del Day of Union Music Store opened up his brain and allowed the riotous world of free jazz to flood in

Somewhat optimistically I always thought that my midlife crisis, if that is what this is, would entail either fast cars or fast women. Or, more hopefully than expectantly, both. Now it has arrived it contains neither. Instead, my middle-aged realigning with 50-odd years of life comes in the form of free jazz. Not even Lamborghini-shaped free jazz, or the avant-garde musk of some sultry leftfield songstress, this is the free jazz of spiritual exploration, political agitation, sonic cacophony and a very direct attempt at redefining the foundations of musical language. It’s not what I had in mind, I’ve got to be honest, but, boy, it’s one hell of a ride.

I’ve been a jazz fan for over 20 years seduced by the wonderment of Blue Note’s musical and visual aesthetic, rubbing shoulders with the giants of Verve and Columbia, basking in the ambient glow of ECM, and tip-toeing through the mainstream releases from OJC and Prestige. Even then I thought I had an open ear to music, a broad liberal approach to jazz listening. Looking back now I realise I was the aural equivalent of a small ‘c’ conservative. I’d go as far as Jackie McLean and anything past that was just written off as either noise, nonsense or just not for me. I’d nonchalantly condemn it with the usual jibes. ‘My three-year-old could do that’ or ‘Christ, what’s this? A fire in a pet shop?’ I thought it was the music of chancers, charlatans squatting the jazz scene with profiles seemingly built on hearsay or controversy. Ornette Coleman and his plastic saxophone… I ask ya?! Sun Ra and his ridiculous stories of intergalactic travel, Cecil Taylor hitting the keys as if Jim Henson had given Animal a piano instead of a trap kit. Ridiculous. It was all just a joke, surely?

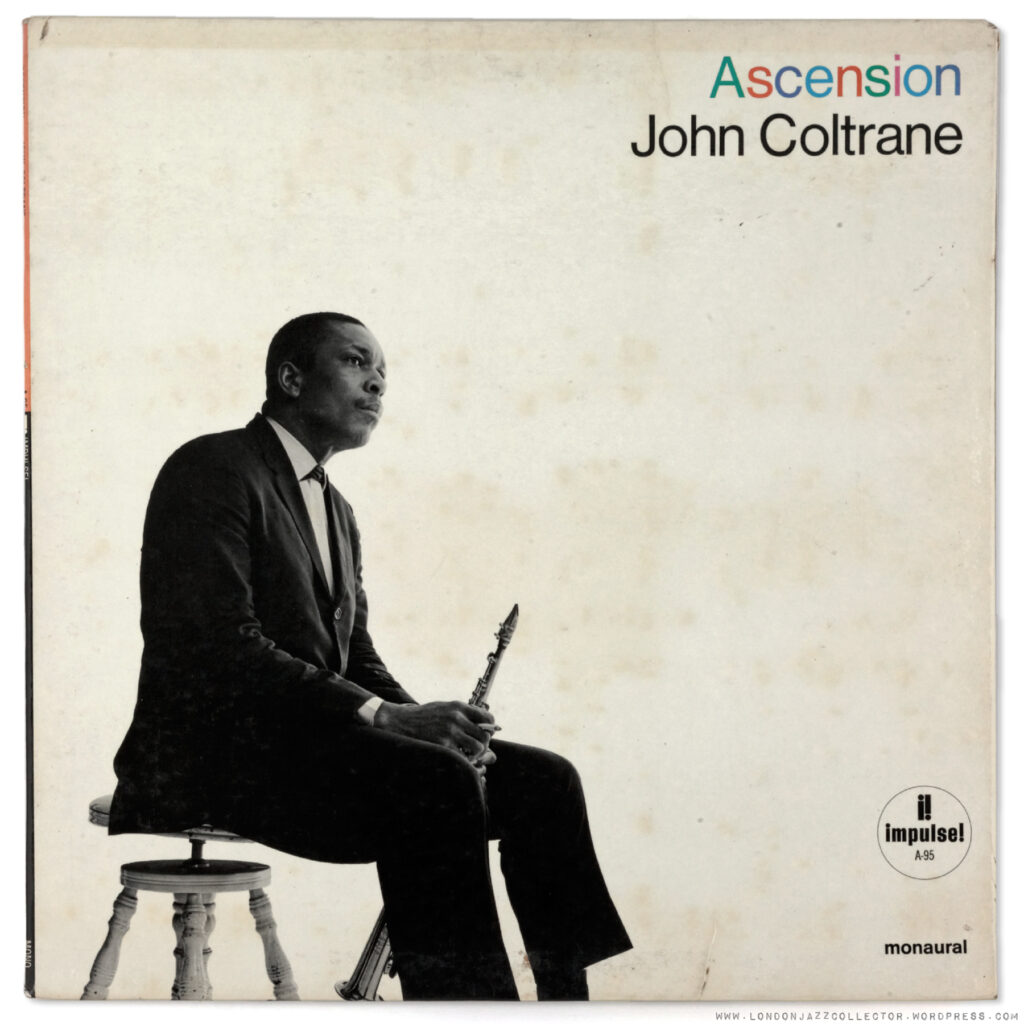

Ladies and gentlemen, I am here standing before you as a living breathing example of how, in a moment of epiphanic enlightenment, everything changes. A packed bus ride home and some random Spotify playlist left to run amok was where, into my unsuspecting ears, John Coltrane’s majestical, otherworldly masterpiece Ascension album poured its mercurial magic straight down my ear canals and into my heart. I got off that bus wondering what had just happened. My head was exploding. I could feel my inhibitions being plucked from my very core replaced with vast, wide-open receptors cavernous in their design. I felt 10 stone lighter and 10 feet taller. I was hypnotised. Even as my ears despairingly sought even the slightest hint of familiarity – a melody, a harmonic whisper, a beat, a simple note that doesn’t sound like it’s coming from a sick animal, anything!! – my head, heart and very soul was being changed forever. I just stopped looking and just let these sounds run riot around my head like sonic mayflies. There was no time to linger, to try and gain a foothold, before I knew it the notes and sounds were gone forever replaced by endless new ones in all shapes, sizes and forms. I was in the eye of the storm and it felt incredible. And it hit me like a ton of bricks. Surely everyone needs free jazz in their lives if it feels this good?

Over the following months I realised I was born again with a new, unwavering purpose of spreading the free jazz gospel to all who will listen which, to be perfectly straight with you all, is not that many. Rather than garner a flock I’ve lost friends, my wife thinks I have gone mad with what she delightfully refers to as “bath emptying music”, and even my greyhound hates me. Yet, like some kind of Ickeian preacher I continue on my road to Damascus and will try here to convince you of its worth. So, where to start?

Every genre has its classics and free jazz is no different. The cornerstones of the scene were laid towards the end of the 1950s and early sixties by the likes of Cecil Taylor, Ornette Coleman, and John Coltrane who we will get to later. These were followed throughout the sixties by disciples – the Marion Browns, the Frank Wrights, the Roscoe Mitchells, the list is endless – and into the here and now with the Zoh Ambas and James Brandon Lewis’s.

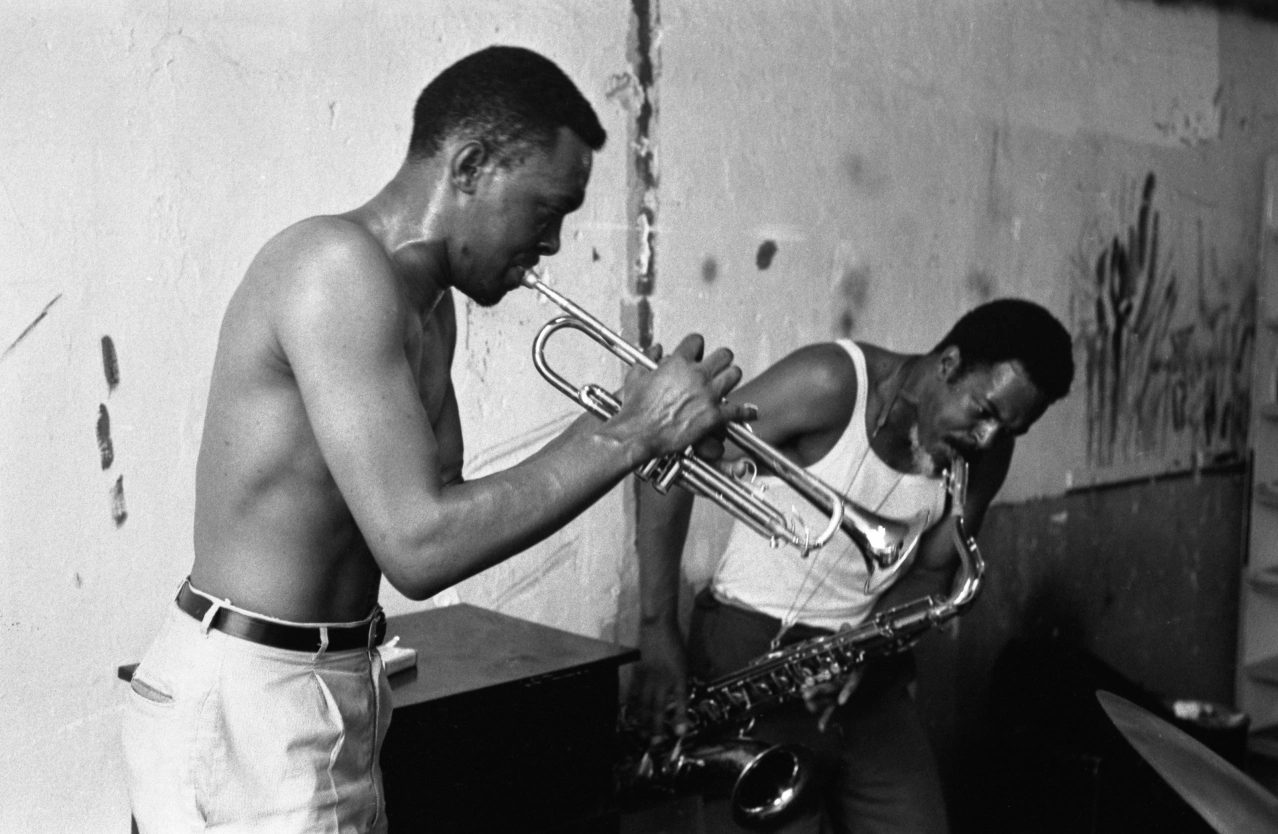

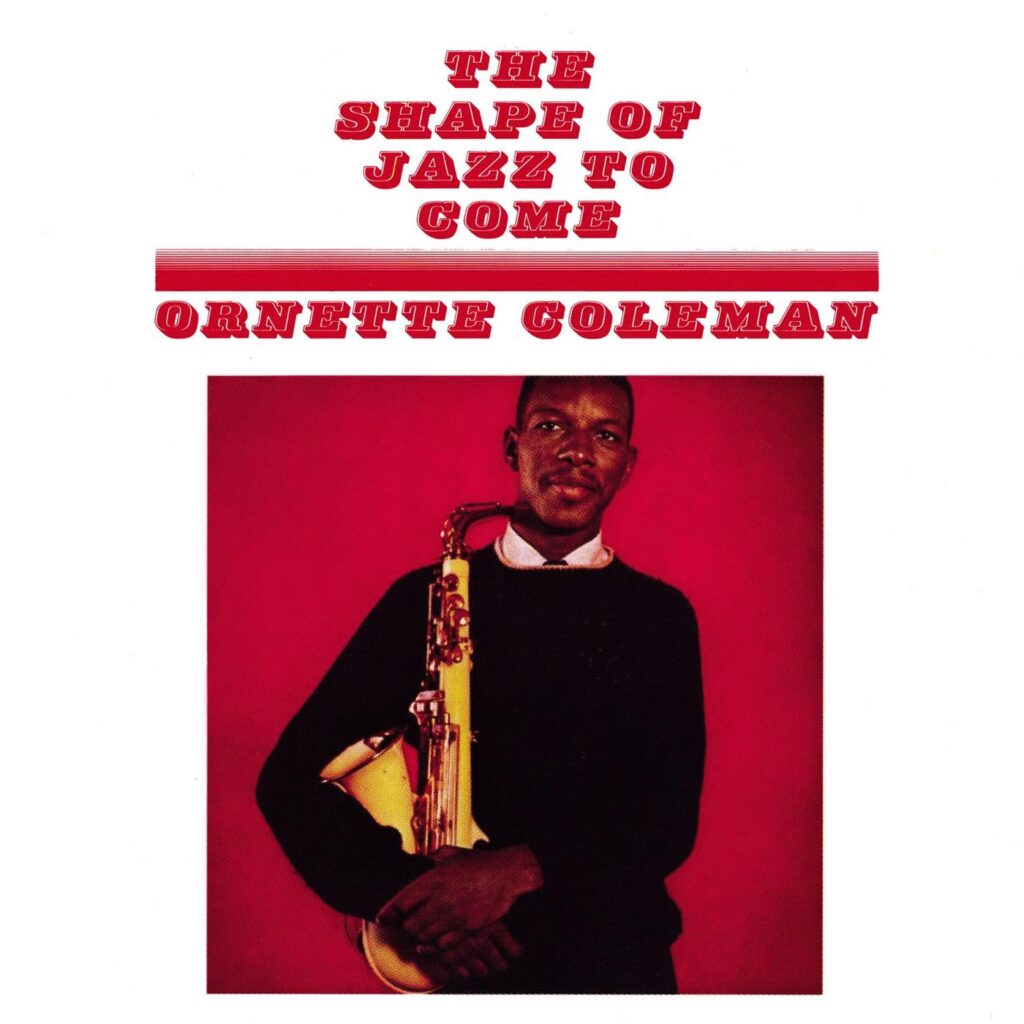

But let’s head back to 1959 which saw the release of The Shape Of Jazz To Come, a quartet album from Coleman alongside his then regular band of Don Cherry on trumpet, Charlie Haden on bass and Ed Blackwell on drums. When you listen to this record now it sounds pretty straightforward, basic even, but within its grooves a new movement was being formed. This was a bop record with a difference, a sparse, barren soundscape where what was left of any melody lines were drawn with stark, dissected and often brutalist design. It’s like listening in on a conversation without ever really understanding what they are taking about. You pick up words or the odd sentence but can’t quite put it all together in a coherent message. Familiar yet somewhat odd.

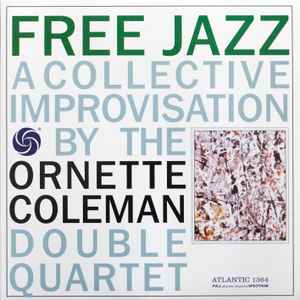

If this was the preface two years later Coleman dived straight into Chapter One with the seminal Free Jazz album on Atlantic. In essence, the album is made up of two quartets playing entirely improvised at the same time. That’s it. Simple. If you listen to the record solely in the left channel you can hear only one group. Listen in the right and you hear the other. Listen through both and you are right in the middle of the maelstrom. It’s quite something to behold even now some 60 odd years later. To my ears it has a childlike playfulness, an impish quality that constantly pushes the ‘To Agitate’ buttons just for the fun of it. In all honesty where it once roared like a new lion on the plains it now purrs like a kitten wrapped in an angora rug. Its importance remains, its bite somewhat deadened. The album certainly caused a stir from the critics. “These eight nihilists were collected to together in one studio at one time and with one common cause; to destroy the music that gave them birth.”

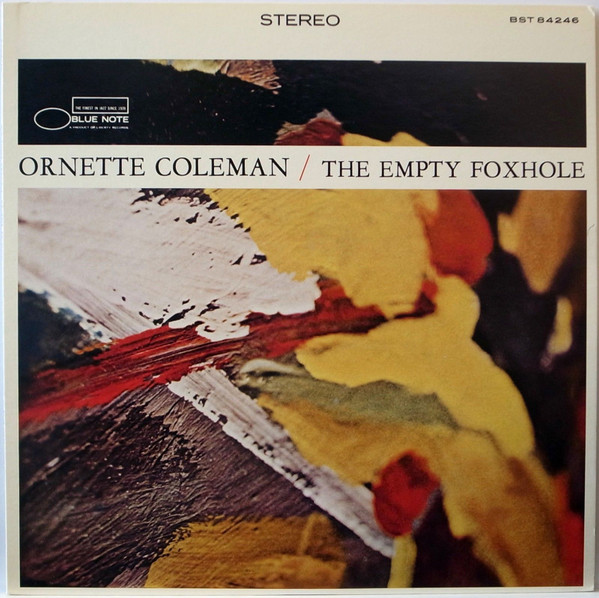

It’s fair to say John Tynan from the US jazz magazine Downbeat wasn’t a fan. His was admittedly one of the loudest voices of opposition to this ‘new music’ but certainly not the only jazzer to bear real hatred towards the way they saw their beloved music being reshaped and reformed. There were those that, similar to the arrival of swing, bebop, fusion, all manner of sub-genres, welcomed what they saw as natural progression. After all jazz has always been exploratory and forward looking. Coleman went on to make a number of extraordinary albums over many years in his quest to invent his own musical language. It’s a grand plan, admittedly, but one he definitely delivered. Even now no-one sounds like Coleman though many try. To cement his position at the free jazz summit Coleman once recorded an album with his then ten-year-old son on drums who was still having drum lessons at the time. Check it out, The Empty Foxhole from 1966 on Blue Note. It really is something.

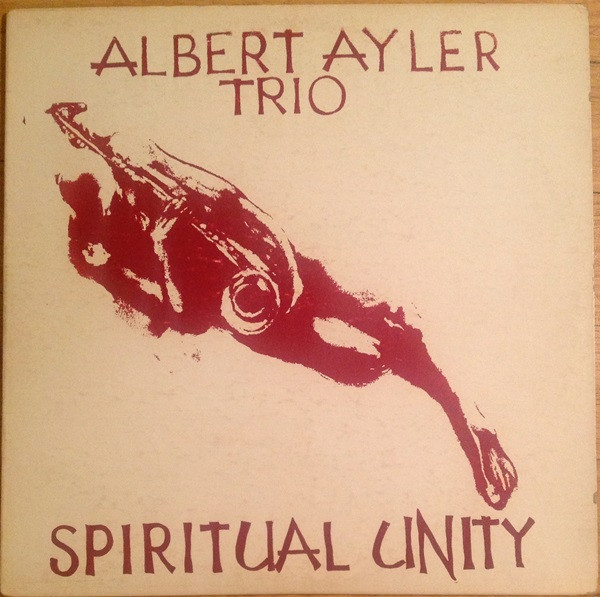

Albert Ayler arrived on the jazz scene like a thunderbolt from Cleveland. Garish, confident, suited and booted in lavish velvet creations it’s fair to say he meant business. A new hip king had arrived. Sadly it wasn’t a straight-forward coronation as he was as welcome as sour beer at most establishments met with both emptying audiences and bandstands. With a tone that mixed old-school church music, an unruly ‘ghost’ vibrato, and sounds from some far off galaxy, he was never going to be a shoe in for jazz royalty. Far from deter him Ayler believed that his music, endlessly fermenting and morphing in his head just had to come out or he’d literally burst and when it was all out, and only then, he would stop playing. His 1964 album Spiritual Unity has become one of my absolute personal favourites.

That is quite a turnaround I can assure you. When I was working in jazz department of HMV back in the 90s we used to play Ayler records, not because we loved them but to empty the shop quick before closing. Jeez, what was I thinking? From the opening bars of ‘Ghosts: First Variations’ there is something both life-affirming and joyous, celebratory even, emanating from the grooves. This is celestial gold, divine music to pierce even the coldest of hearts. That makes it sound an easy listen, right? It’s anything but. What follows is a slow dissembling process of any form of harmony or melody, replaced with layer upon layer of accents, falls, squalls, guttural outpourings at times so visceral they make you jump, infiltrating an ever-constant ‘conversation’ between drummer Sonny Murray and bassist Dave Holland. Moments sound familiar, occasional fragments of a ‘tune’ float by on the river of perpetual motion but never slow enough to grab hold of them. Before you know it they are far, far downstream being dragged under by the next current of ideas, gestures and creativity. It’s an exhilarating, magical ride that just knocks me sideways every time I hear it. It’s important to note Spiritual Unity is a long way from the full-on aural assaults of other free jazz albums and that’s what makes it so special.

The wonderful trumpeter Kenny Dorham, much respected and loved in jazz circles gave the record zero stars. “Not worth the paper this review is written on” was his verdict. Harsh? sure. Correct? Absolutely not. Spiritual Unity has more than stood the test of time and sounds as remarkable as it must of done on release. Six years later Ayler was found dead floating in the Hudson River. Even now the debate rages as to how he died. Some say suicide, some say he was whacked by the mafia. Regardless of what is true it all adds to the mystique and magic. He produced music that really can only come from someone truly committed at the source, a deeply ‘human’ sound that one minute can tear your heart in two and in another leave you gasping for air. A full immersion in Ayler’s work is a must as is checking out Richard Koloda’s excellent ‘Holy Ghost: The Life And Death Of Free Jazz Pioneer Albert Ayler’ which is a great read for sure.

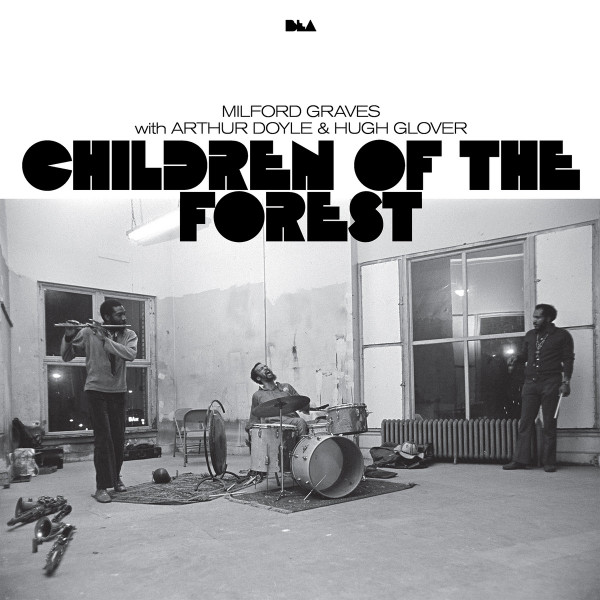

If you were to read any plotted history of free jazz the likes of Free Jazz and Spiritual Unity will feature in every one in bold letters. They are fundamental releases on a scene that was still finding its way and were recordings that set the benchmark – and framework, essentially – for much of what was to come. That’s not to say they set out any rules. Quite the opposite, they tore up the rulebook. As a consequence free jazz comes in all colours, sizes and disguises. It takes on different forms. Whereas the likes of Milford Graves and Arthur Doyle (Babi or Children Of The Forest lovingly reissued on the Black Editions label are must-haves!) were looking to eradicate years of jazz conformity and return the music back to the wild, joyful, ritualistic celebrations of African tribes, Roscoe Mitchell, The Art Ensemble of Chicago, and their ilk took a way more collegiate approach and looked to liberate tired, dated opinions of what jazz ‘should’ be or was and focus their attention on the meaning of sound itself. Whereas Frank Wright and Archie Sheep were sonically preaching African-American equality and resistance, Sun Ra was selling one-way tickets to Intergalactic peace. They are chalk and cheese in their objectives yet all draw from the same freedom well. The other important thing to remember is that all of these musicians choose to follow the freedom muse. All come from long, solid backgrounds in the mainstream, seasoned musicians and technically able. They didn’t just land here from another planet and start playing noises on nose flutes and finger bells. They are driven, compelled even to explore the outer reaches of the musical stratosphere in search of sound and aural discoveries. I say this as it’s sometimes easy for the naysayers to point to certain records or performers where it sounds like they have never seen an instrument before let alone played one. That really isn’t the case.

Take John Coltrane and Cecil Taylor, arguably the two mightiest warriors in the ring. There is no arguing Coltrane’s pedigree within jazz. His work all through the 50s both as a leader and sideman with Miles Davis is up there with some of the greatest music in jazz history. Then it all changed. From the early 60s Trane set his sights on something far off in the distance, God essentially, and began talking in a language that became more and more accented as the years passed. In essence here was a musician writing music solely for a higher being with complete disregard for any commercial or artistic needs. Trane was on the bus heading to the stars and, although welcome to join him your presence was neither needed or acknowledged. Diving into his albums post the seminal A Love Supreme you will be hit by the sheer intensity of it all. It’s face-melting stuff some of it, like the Live In Seattle album or posthumously released Stellar Regions, which is as visceral (and undeniably beautiful) as he gets in truth. Imagine getting roughed up by angels. In a free jazz sense it wasn’t so much Coltrane’s music here that is the focus of the adoration, it’s his unrelenting will to fulfil his spiritual goals through the music. If you are to truly embrace the genre then Coltrane is essential listening. Start with either the aforementioned Ascension or, for what is a slightly easier introduction, the duo record with Rashid Ali Interstellar Space from the year of his death,1967. Strap in, the clue is in the title. There is nothing difficult about this music. The opposite in fact as this is music that is a pure as driven snow, untarnished by anything but pure, simple, honest, heartfelt love.

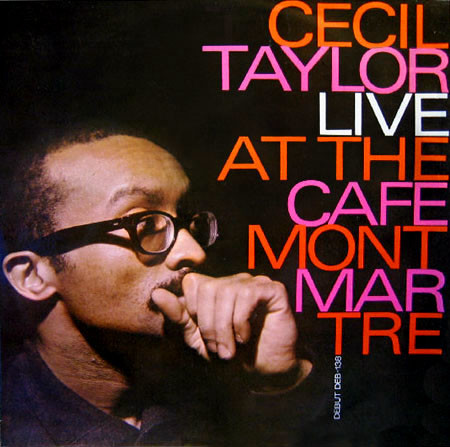

Cecil Taylor is an altogether more awkward proposition. Here is a pianist who from the very beginning musically it was clear he had eyes on other prizes mainly the ones high on shelves marked ‘open with caution.’ A whirling dervish of angst, intelligence, defiance and unique mannerisms, Taylor approaches the piano as if meeting both friend and foe. Breakneck notes and runs, all played with the precision of a brain surgeon, build layer upon layer of sound into giant towers of crescendo before collapsing with a myriad of sounds escaping into the air like dropped pearls on a marble floor. Then it all begins again. Listening to Cecil Taylor is being right on the edge of the gorge looking into the giant abyss below. One wrong note, one slipped chord and you will fall. Yet, and this is the genius of Taylor, he never lets you fall. He never misses that note, he never fumbles that chord. There are very few musical moments that surpass Taylor in full flow, it’s the thrill of the best ride at the carnival. Times infinity.

Start with Live At The Cafe Montmartre (or Nefertiti The Beautiful One Has Come to give it its proper title) an extraordinary trio set from Copenhagen in 1963. I choose this wisely for free jazz virgins as in Jimmy Lyons, the saxophonist on this date, you have a willing guide to lead you in and out of the music. His ‘mainstream’ background enables him to offer some welcome and familiar refrains whilst either side of him Taylor and drummer Sonny Murray systematically take the roof off the place. I’d also check out some of the later solo records – Likes of Indent or the extraordinary Silent Tongues from 1975 – where the protective screens are down and you are open to the full ferociousness of Storm Cecil.

Ok, look, I get it. Listening to this stuff isn’t easy and no matter how I spin it here there are gonna be times when you are listening to this music and it really doesn’t make any sense at all on any level. It’s a shock. It will probably give you a headache. You will question yourself. “Do I REALLY like this stuff? Am I just pretending? Am I just desperate for something new to experience? There have been times when I am listening to albums that sound like I am sat inside a vacuum cleaner while its hoovering up a particularly troublesome litter tray.

But what I can say, and I say this as truthfully as I can, in the maelstrom, in the deep, deep heart of all this music is where the real unfiltered joy is there both for the musicians and you, the listener. In amongst the squawks, squeals, atonal beats, the shouting and screaming, the barrage of noise lies their and your Nirvana. This may seem the deranged rant of a man numbed and clearly punch-drunk on this stuff but mark my words. It will happen to you too. There is nothing to be afraid of when it comes to free jazz. I have merely touched upon the tip of an iceberg that will take down any unsuspecting ships especially those with familiar destinations. Wait till you hit the Eastern European scene or explore dark, squalled Japanese basements where musicians such as Abu Kaoru and Toshinori Kondo will remove any resistance left in your heart in indescribable ways.

Further listening

Some records to set you off on the right foot

Black Beings, Frank Lowe (ESP-Disk)

Afternoon Of A Georgia Faun, Marion Brown (ECM)

Historic Music Past Present Tense, Peter Brotzmann/William Parker/Milford Graves (Black Editions)

Kingdom Come, Charles Gayle (Knitting Factory)

Your Prayer, Frank Wright Quartet (ESP-Disk)

Sound, Roscoe Mitchell Sextet (Delmark)

Giuseppe Logan, Guiseppe Logan Quartet (ESP-Disk)

Black Paladins, Joseph Jarman (Kepach Music)

Other Afternoons, Jimmy Lyons (Actuel)

Homage To Africa, Sonny Murray (Actuel)

The Flower School, Zoh Amba / Chris Corsano / Bill Orcutt (Palilahia)

And read:

As Serious As Your Life, Val Wilmer

Coltrane: The Story Of A Sound, Ben Ratliff

How To Listen To Jazz, Ted Gioia

Universal Tonality: The Life And Music Of William Parker, Cisco Bradley