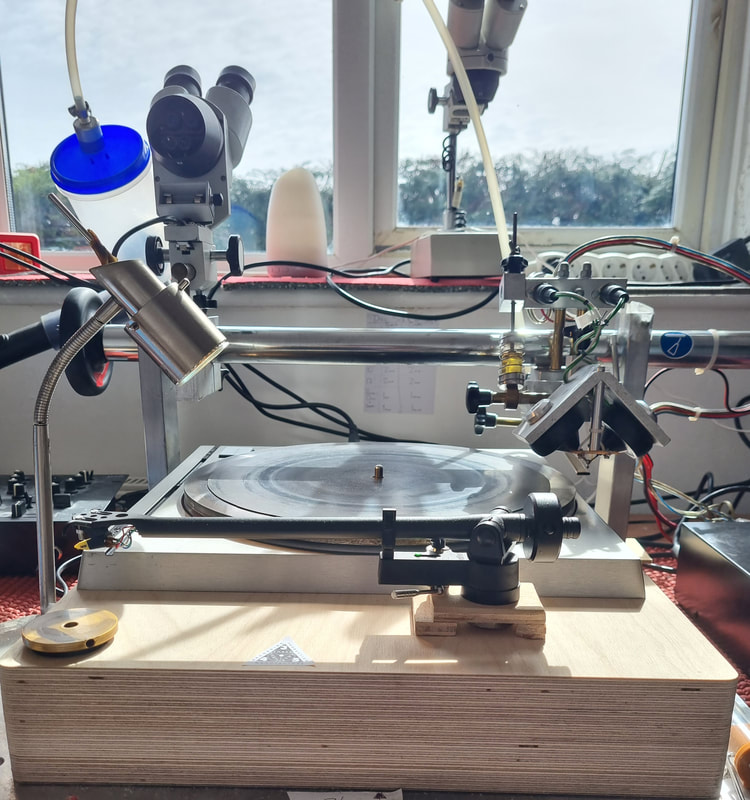

Lathe-cutting whizz Phil Macy of Brighton’s 3.45RPM has been carving out records of all shapes and sizes for over a decade now. We trade cutting remarks with him

Could you briefly explain the lathe-cutting process?

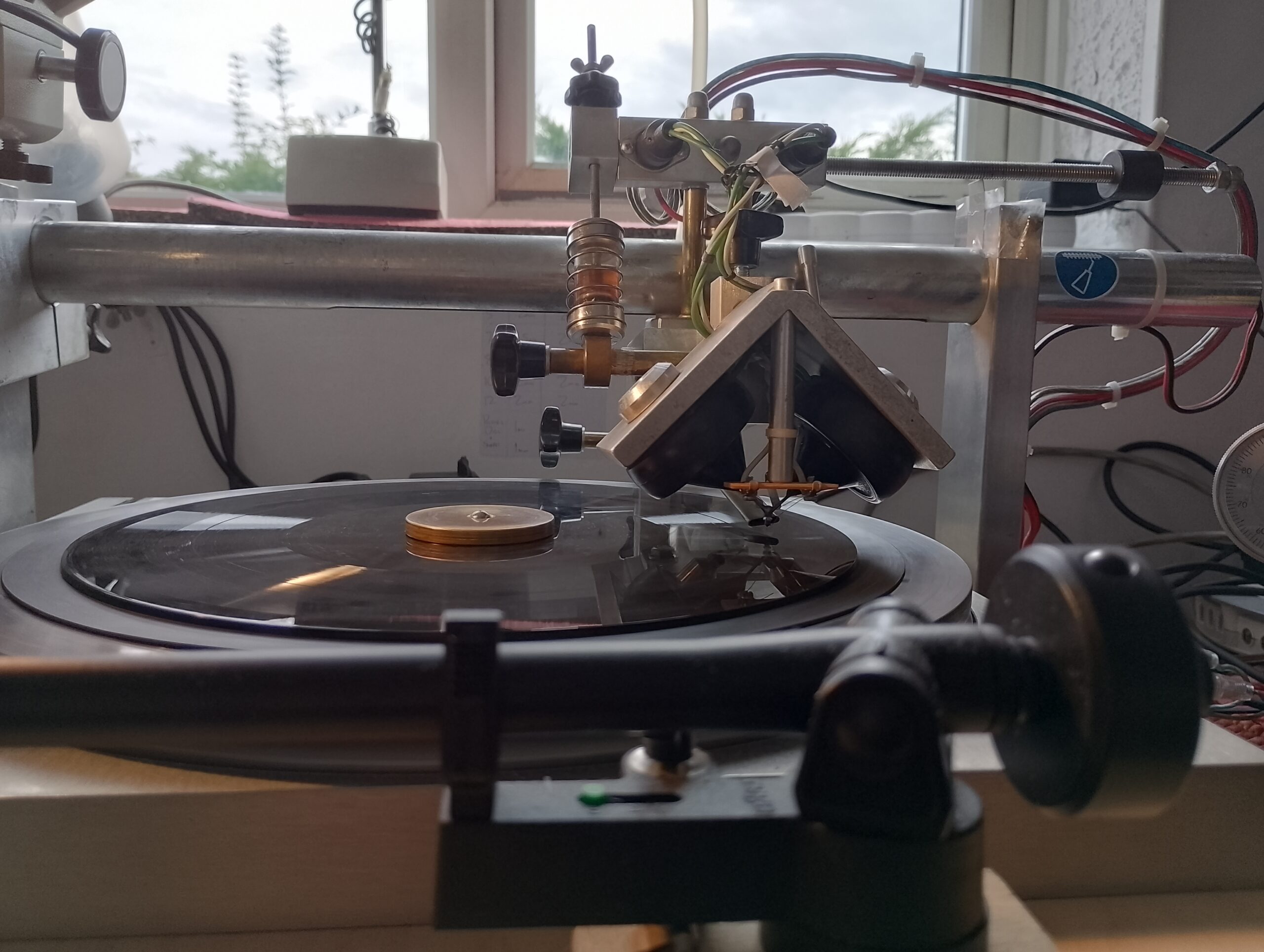

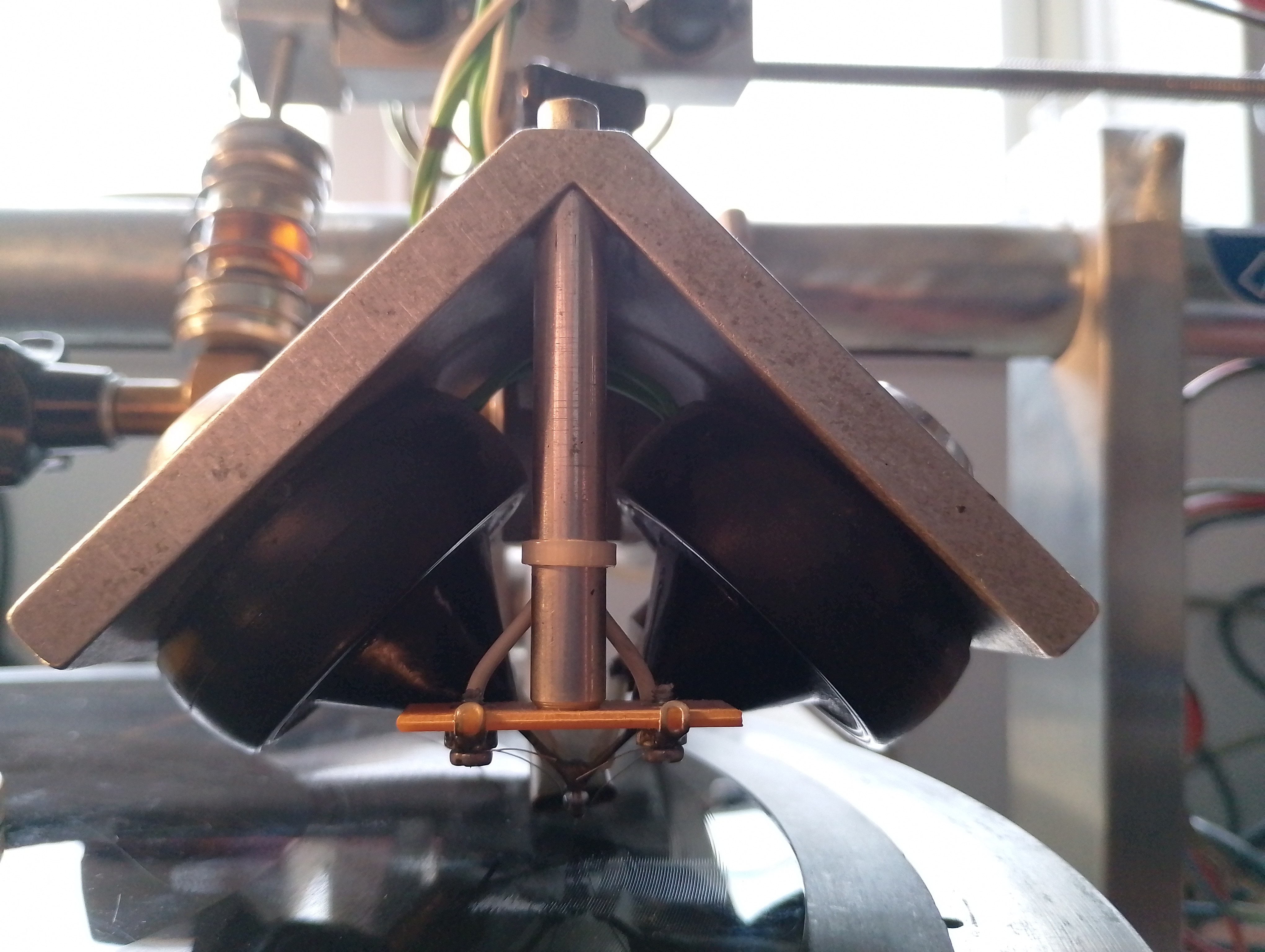

Lathe-cutting is the transfer of sound onto a disc. All records start out as lathe cuts, but the majority of discs in people’s collections have been pressed, which requires the initial lathe-cut acetate to be turned into stamper plates, which in turn can be used to press hundreds of identical records in a single day. The difference with what I’m doing is that I cut each disc – one by one, in real time – onto a playable, durable disc.

The obvious disadvantage to this is it’s a significantly slower process than pressing records, and, as you have to listen to each and every disc while it’s being cut for the purpose of quality control, it is a hugely repetitive business. It takes a sturdy constitution to listen the the same LP 50 times in a week, however much you may or may not be enjoying the music! The time-intensive nature of it can also make it a relatively expensive business. Having said that, in the ten years I’ve been involved with lathe-cutting, the price gap between pressed vinyl and lathe cuts has come down considerably.

The plus sides are many, though. With pressed records, you’d be hard-pushed to find a pressing plant that will touch an order of fewer than 100 copies – some won’t even consider less than 500. For the vast majority of artists, this has always made vinyl an unrealistic prospect. The reality is, you’d end up with dusty boxes of unsold product under the bed and a large, unrecouped dent in the finances. Most artists just don’t have a big enough fanbase to sell to. However, with lathe-cutting, you can tailor the amount you order to demand. So if you only get pre-orders for a dozen records, you can just get a dozen done. It’ll cost a bit more per unit, but at the same time, you get a rarer, more exclusive artefact, which, by its very nature, makes it better value for money.

Do you have a typical client? I’m envisioning young indie bands who’ve never released a record before.

Not as such. There’s certainly a growing market of younger bands interested in records as a merch product, which has made up a good percentage of business over the years. I’ve cut records of small-run early releases for the likes of Kid Kapichi, Hot Wax and SNAYX – bands that, at the time, would not have been big enough to make it worth investing in a large run of vinyl. But they took the plunge with highly limited lathe-cut releases, and the records have gone on to be heavy collector’s items. It may not have been a huge payback on the outlay, but it’s been great for publicity.

I’ve also had dealings with acts who’ve been quite open about the fact they don’t think their fanbase has any particular interest in records, but have wanted a lathe cut available just so they can have copies for themselves. Bands coming to me for ‘just the four copies’ is a reasonably common occurrence!

“For a while in the early 1900s, lathe-cutting became the profession with the highest suicide rate in the industrialised world”

Having said this, it would be fair to say that I got my initial foothold in the business of lathe-cutting thanks to a few ‘established’ names in the world of small, independent, underground labels. My very first cut was for the wonderful Geoff Dolman at Static Caravan, who at that point was already 15 years and 300 releases in. Quickly after that came the first Polytechnic Youth cut, via Dom Martin, who’s been involved in a fair number of extremely hip indie labels and releases over the years, including Earworm, The Great Pop Supplement and Feral Child.

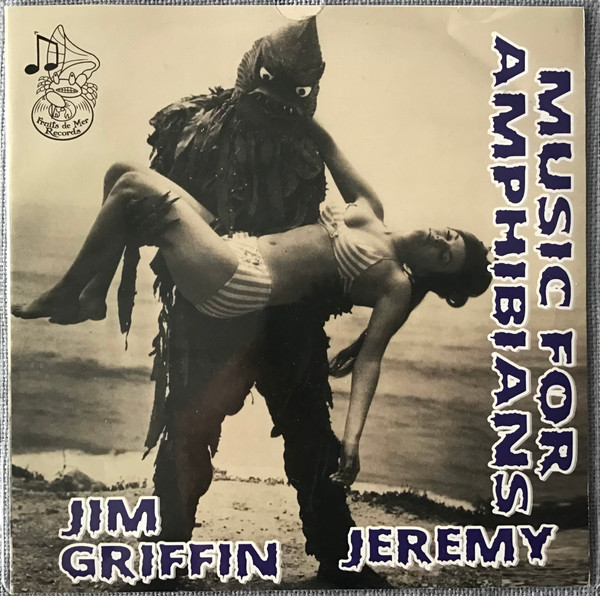

I then also had the great fortune to link up with Keith Jones at Fruits de Mer Records to start lathe-cutting for his side label, Friends of the Fish, which led to a widening inroad into a very diverse and far-flung psych scene. A year or so after that, I started cutting FOTF records for bands from places as distant as Norway, the Philippines and the US, which really helped spread the 3.45RPM name.

Aside from all this, I do get plenty of requests for one-offs – birthday present picture discs, old demos of bands people were in years ago, art students wanting a couple of discs for presentations… It’s thankfully quite a varied field I deal with, otherwise it could get a bit dull. I do love the truly odd requests that come in!

Why do you limit the runs you offer?

In the late-1800s – before universal electrical access and the existence of pressing plants – lathe-cutting was the only way records could be manufactured. If a tune became a ‘hit’ and sales took off, then it would take hundreds of lathe cutters working around the clock, cutting thousands of the same record to keep up with demand. There’s a story about how, when the famous old music hall track The Laughing Policeman became popular, it was selling so many that lathe cutters had to work around the clock for months on end to satisfy the shops and distributors. They were cutting the same song over and over again, and as a result, a number of them went completely mad. For a while in the early 1900s, lathe-cutting became the profession with the highest suicide rate in the industrialised world. So, I’ll keep to 100 seven-inches or 50 12-inches of the same recording, thanks.

How does a lathe-cut disc compare to standard vinyl? Is there a difference in sound quality?

My own estimate of the cuts I produce is that they sound maybe 95 percent as good as standard pressed vinyl. Maybe some cuts will fall a little under that, maybe some sound as good as the ‘real thing’, but on the whole, it’s close enough that there shouldn’t be any complaints. In fact, I’d go as far to say that most people wouldn’t notice a difference on everyday listening. I would never personally claim that my cuts sound as good as pressed vinyl, as the maths just don’t add up: if someone has spent a million pounds on setting up a pressing plant, I think it would be disingenuous to pretend that a small home setup in a spare room, which cost 2 percent of the price, would be able to fully compete. I tend to make the comparison between racing a Mini Metro against F1 cars at Brands Hatch, and still finishing in the top ten. It’s remarkable that such a small-time setup can come up with such a relatively high quality product.

Home and DIY lathe-cutting has come a long way in the past two decades, though. Hissy, tinny, low-volume etching onto picnic plates and greenhouse panels has, on the whole, been replaced with a far fuller and more complete sound. And there’s a lot more knowledge available online, thanks to sites like The Secret Society Of Lathe Trolls, which has become a primary source for cutters, both professional and amateur, worldwide to share their experiences. Also, the creation the Souri Vinylrecorder T560 has led to a much wider circle of people, globally, having the facility to cut to a specific standard.

“I do get plenty of requests for one-offs – birthday present picture discs, old demos of bands people were in years ago, art students wanting a couple of discs for presentations”

Are they cost-effective?

If used in a considered way, then very much so. It’s just a case of focussing on the pros, and knowing what cons to avoid. The important thing to grasp about lathe cuts is that, at the end of the day, there doesn’t have to be any dead stock. You can tailor the order to the exact amount required by using pre-orders, basically guaranteeing a sell-out on release, which is not only good for the finances but also looks great in terms of publicity.

For any act who know that they can sell over ‘x’ amount of copies (say, 200 seven-inches), then I’d usually advise looking at getting a pressing done, as it’s much cheaper per unit. Even if you end up with some unsold stock, you should still be able to recoup the outlay – unless you wildly over-order. But for anyone who thinks 100 seven-inches may be pushing it, then lathe cuts are undoubtedly the way forward.

It’s also interesting to note the price of some standard seven-inches in shops these days. They’re very often £15 for a record that has been pressed in its thousands. At that point, the cost of lathe cuts starts to compare very favourably.

What non-standard sizes do you offer? I think I’ve got a non-standard Irma Vep lathe cut, was that you?

All sizes are available, within sensible limits. The smallest discs I’ve cut were two-inches, and though I’ve never personally cut a disc larger than 12-inches, there are 14-inch discs available. In the 1930s and 1940s, 16-inch transcription discs were often used for radio, but I do not have the facilities to cut one of them – before anyone asks.

In between that, I’ve dealt with pretty much every size going. It’s possible that Irma Vep was an eight-inch cut I did for Endless Records back in 2017. I did a few eight-inches for Endless – Sloath was another for the label. It’s a great size for artists whose average song length is above the standard pop size of three to four minutes. Some people aren’t really happy with the awkward nature of eight-inches, though. They won’t fit nicely into your seven-inch collection. But on the plus side, you can get a good seven minutes on one without having to cram in the grooves or lower the volume too much, which can make it a great budget option rather than going up to the slightly more standard ten-inch.

Also popular are five-inch discs. These are nice and cheap – you can fit around two minutes of audio comfortably, and because they’re CD-sized, they can be stored and filed reasonably easily.

Shaped discs have also become a bit of a thing recently. With those, the only limit is your imagination. And having a cuttable playing area. But apart from that, you can be as creative as you can get away with. I released a ‘stars within a star’-shaped disc a few months ago, for Kawabata Makoto from Acid Mothers Temple: a spectacular, 12-pointed star disc that then had tiny stars cut into each of the 12 points. Not exactly cheap to produce, but once it was housed in appropriate packaging, it was one of the most beautiful items I’ve ever had the pleasure to be involved with.

What inspired you to get into the lathe-cutting business? Where did you get your kit from?

Well, without the legendary Pete King, I guess it would never have occurred to me that you could buy a lathe unit, set it up in a spare room and then bang out discs on demand. Pete is a guy in New Zealand who, in the early 1980s, bought some old record decks from a radio station, modified them to manufacture polycarbonate discs with, and created a whole scene in NZ – and then beyond – of weird, off-kilter tiny-run releases. The scene grew in popularity throughout the 1990s, with orders from the likes of Beastie Boys and Sonic Youth. I bought my first King lathe in around 1995, which would have been a Handful Of Dust half-picture-disc – music on one side, a picture on the other. By 1997, I’d ordered 38 copies from him of an album that my band at the time, Kashmir Twist, had recorded. From then on, it was always on my mind to manufacture my own product, keeping it as independently pure as possible – being able to release whenever I wanted, rather than waiting for a label to pick up on things, or having to wonder if I had enough market to afford a full pressing.

Records have always been my preferred format for both listening and releasing. I didn’t even buy a CD player until around 1998, which was pretty late, and the whole CD-R scene never caught my interest in the way vinyl did. CD-Rs were/are absolutely superb items for the DIY ethic, and I own hundreds of them by cool artists who never would have been able to put their music on record. But the ease of obtaining them always made me feel they were somehow less ‘dedicated’ than a record. I can’t argue against this being an elitist and snobby attitude to a format that enabled DIY artists to carry on releasing some beautiful and affordable art, but hopefully people can understand what I mean.

Anyhow, how I acquired the lathe was that I’d been promoting shows in Brighton for a dozen years or so, but had decided that I wanted to move on and do something different. This tied in with a slightly insane idea I’d developed around my upcoming 45th birthday – namely that, on the day of my 45th, I’d start the 454545 project: a series consisting of 45 seven-inch discs of music I’d played on that played at 45rpm, and in editions of 45. And it would all be done by my 46th birthday. So basically, a seven-inch every eight days or so for a whole year.

I worked out the finances of getting this done via pressing plants, and it was completely unfeasible. Even if I’d been able to find a manufacturer prepared to take on such a bitty, minor project, and then deliver on time each week for a year, it would have cost in the region of £40,000 – at a conservative estimate! So, the only way I could possibly achieve what I was planning, was to own the means of production. It was then that I started looking into lathe-cutting.

There seemed to be only one person in the world who was making lathes on an off-the-peg basis: a German guy called Souri, who originated the Vinylrecorder T560 – or the Souri as it is commonly known. The only problem was that he’s very cagey about who he sells machines to and it took months to gain his trust, but he finally agreed to let me come over to Germany and see how the lathe worked before selling it to me. A big part of obtaining the machine was for purely selfish reasons, but once word got around, the business side got popular, very quickly, and soon took over the majority of my time.

“Discogs currently has a disc I cut for Polytechnic Youth in 2015 on sale at nearly £700”

You recently celebrated your tenth birthday as a lathe-cutting concern. Is it a skill you get better at with experience? And how has your business/approach changed over that time?

I was completely in the dark about lathe-cutting before I travelled to Germany to buy the machine. I knew nothing of any value on the subject. Ten years later, I now know a bit, but I’m a long way from being anywhere near what I would consider an expert. This is maybe the best part of the whole thing – I’m learning new stuff every week, every day even. I’m not a great technical mind. I’ve always been happy to just plug something in, and if it works, then that’s good with me. I’ve never been bothered about the physics and workings of it all. But the lathe has definitely changed my outlook, and now I’ll actively search out and consume as much information as I can get. I view it like an ongoing Open University course, but one I don’t expect to ever complete.

In which formats do you need to receive the sound files?

In theory, I can cut from pretty much any sound source, as long as I can transmit the audio to the cutterhead. Because it’s just a case of blasting sound waves at a needle, which transposes those vibrations on to a physical surface, you could, if you had a very large and loud megaphone, produce a sound by shouting closely at the needle. This is pretty much how recordings were made up to the 1930s. However, more practically, I tend to work from WAV files.

Having said that, one of my favourite discs was a one-off birthday present for the bassist in an old punk band called The Plague. I was sent an original cassette they’d made back in the day, and was asked to cut the album directly from it, thus avoiding any digital involvement in the finished product. It was extremely nerve-wracking doing the cut, in case the tape buggered up, but the finished sound was actually superb. I hear the guy was overjoyed with the final product.

Are certain genres of music unsuitable for a lathe-cut disc?

None that I’ve come across. I’ve cut everything from ambient to industrial, and just about everything in between. As long as it’s set up right, then anything should be possible to cut with a near-perfect finish.

Maybe difficult to answer, but do you know of any lathe-cut collectibles?

This is probably the easiest question you’ve thrown at me! By their nature, lathe cuts are, generally speaking, all limited edition and rarer than your average shop-bought disc. So, it’s an inherently collectible format, and as such, prices can very quickly reach extreme heights.

As far as I know, the Kid Kapichi seven-inch I mentioned earlier – Ice Cream, 50 copies only – has never come up for sale. That would probably command a fair price. The SNAYX seven-inch I issued on Gardener’s Delight in 2021 went for £70 a few months back.

Discogs currently has a disc I cut for Polytechnic Youth in 2015 on sale at nearly £700, though it has been up there for around eight years now, so I’d say that’s a tad optimistic. However, there are plenty of cuts out there which regularly go for over £100. I’d guess the signed, hand-screened Silver Apples/Andrew Weatherall 12-inch is one of the most future-proofed in terms of longevity, but there are releases from the likes of Alison Cotton, Smote and Kombynat Robotron, 12-inches on Weird Beard, a few artists on the Sonic Cathedral label like Bdrmm and Deary, pretty much all the Friends of the Fish label cuts I’ve done, and Feral Child’s ongoing film and interview series, which always sell out right away then often get flipped on selling sites.

In all honesty, I’d rather people didn’t do that. I have no problems with a record gaining value over a period of time due to an organic wants-v-availability symbiosis, but the flagrant buying of highly limited and desirable items purely to instantly add 400 percent or whatever to its value is a cold way of going about things. It’s not really a true music lover’s’s ideology – just a capitalist scrape. But I understand people need to make money, and it can add kudos to both artist and product, so hey ho.

Could you name some favourite projects you’ve worked on over the years?

The aforementioned Silver Apples/Weatherall 12-inch has to be in there, as would a lovely square eight-inch picture disc called Mrs Hawkwing’s Space Jam, which was led by the late, great Nik Turner and his cosmic sax playing. The Sunday Experience memorial seven-inch for the music writer Mark Barton was a bittersweet joy to work on, with all the bands involved giving it some top tracks. I cut a one-off picture disc of it which made a couple of hundred quid for a cancer charity. I started a label a couple of years ago called El Ron Del Mundo, and have had the pleasure of being able to release discs by such long-admired artists as New Zealand’s Roy Montgomery, as well as that star-shaped disc from Kawabata Makoto.

There’s too many to list, in all honesty. I could go on for paragraphs. I do consider myself very lucky to be constantly working with such a wide array of fine bands, artists and labels. I’ve fallen on my feet with this line of work.

However, I think there’s one disc in particular that I always consider to be the very epitome of what is wonderful about owning a lathe-cutting machine. You can be as creative, thoughtful and one-off as you want because you’re not trying to please a wider market and garner sales. It’s for when you just want one record, on one disc, for one person. A couple of years back, I received an order for a seven-inch which was intended as a gift someone wanted to give their partner. It was a one-sided seven-inch with four minutes of completely silent groove, except for right in the middle, where a woman’s voice softly said, just the once, “I love you, Dave.”

Every time I think of that record, I think to myself: “That’s why I love this job.”

For any lathe-cutting needs of your own, you know where to go: www.345rpm.com